LYV: Monetizing the Moat

-LYV is often dismissed on the buyside because of its complicated financials, visceral hate from customers over Ticketmaster fees and near constant DoJ investigations.

-The moat is incredibly strong (scale, switching costs, & cornered resources) and Live Nation is often at the fulcrum points in the value chain for live events.

-Despite the hate they receive, LYV is the demand and supply aggregator of the industry and is pivotal to the economic value of live events for all stakeholders.

-Historical focus has been on the profits in the high margin areas of ticketing and sponsorship. Over the medium term the bigger opportunity is going to come from re-investment back into owning or operating their own venues.

-This will lift the returns on capital while also denting regulatory risks over time.

-LYV is trading at an attractive absolute level and low relative valuation versus history in front of an acceleration in profit growth.

This is not investment advice. Investing is dangerous, often painful, and possibly hazardous to both your financial and mental health. Do your own homework.

When diving into Live Nation there are plenty of reasons to put the name into the “too hard” pile. The accounting and disclosures are a mess. There is open debate to what true owners’ earnings look like (it certainly is not the adjusted free cash flow or AOI that management touts). The company looks capital intensive and strikes numerous minority and JV investments that further muddy the waters. GaaP EBIT margins are low single digits and EBIT dollars fluctuate widely. Your average value investor will find it impossible to plug Live Nation into a traditional McKinsey DCF model and see a pretty picture. Many long-only investors I know give up on the name about a third of the way through reading the 10-k.

The rest reject it for qualitative reasons. Live Nation is the punching bag of the industry, rightly or wrongly despised as a greedy middleman by customers and some artists when operations are not meeting expectations. The 2023 Taylor Swift debacle angered so many people that even our esteemed leaders in congress turned their ire on the company. The industry can appear brutally competitive and opaque to outsiders, with participants having a reputation for being sharks pursuing zero-sum interests. Worst of all, the DoJ shows up every few years (including 2023) with allegations of abuse of their monopoly power creating constant fear that the company could be literally or effectively broken up.

Still, when taking a step back from these faults I find the business attractive. There have been multiple attempts by competitors to attack Live Nations’ moat or circumvent their power with little success. Market share data is tough to come by, but from what I can gather market share is stable with slow shifts in Live Nations’ favor over time. This speaks to some sense of industry rationality. Both artists and customers have struggled to free themselves from Live Nations’ grasp, and even some of the largest touring acts that tried to go independent have admitted defeat and returned to working with Live Nation because of the value the company provided. While anecdotal, the customer experience on their platform has improved dramatically over the last decade as the company re-invested into their offerings. The durability of their market power and the constant DoJ investigations likely speak directly to the strength of Live Nations’ moat.

Adding to my attraction, the entire music ecosystem seems much more symbiotic than the industry’s reputation would have you believe. Competitors and customers sometimes berate Live Nation, but most industry insiders I have interacted with speak highly of the value Live Nation creates for their stakeholders. While streaming has likely single-handedly saved the music industry, live touring is still the key source of income for artists and live concerts do not seem to have the threat of digital disruption that other industries face. In fact, as streaming grows internationally and music moves beyond just local taste, the opportunities for global tours should be a tailwind for the company.

Most importantly since the end of 2011 Live Nation has delivered a TSR of 20%+ crushing the S&P 500 despite the non-stop hate that the company gets and a near death experience during Covid.

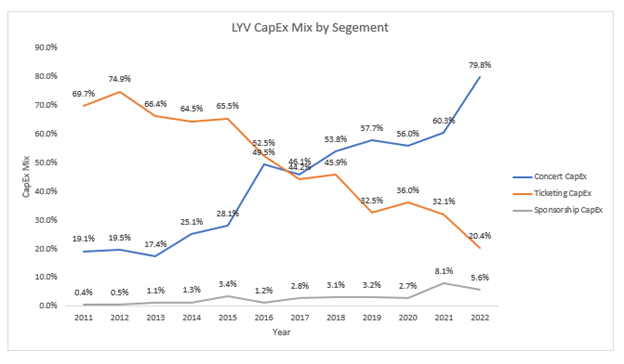

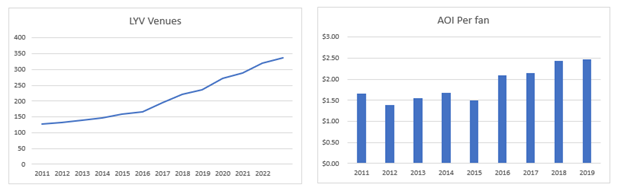

Prior to this run, Live Nation struggled to really capitalize on their position. Coming out of the Great Financial Crisis they began to focus on monetizing their sponsorship business and acquired Ticketmaster to strengthen their position in the ecosystem. These high-margin areas have been the focus for most investors for the last decade and are deservedly seen as the gems of the business. Starting in 2016, management shifted their priorities to focus the sites they control directly (including an important inroad into festivals) and better monetizing fans at their own events through concessions and add-ons.

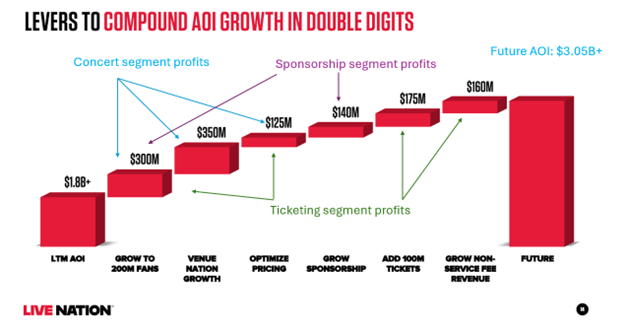

From 2011 through 2019 Live Nation doubled Adjusted Operating Income (~$440M in 2011 to ~$940M in 2019) mostly on the back of Ticketmaster and Sponsorship. To achieve their vision of getting to $3B+ in AOI they are going to re-double their efforts on their venues, which should further strengthen their demand aggregation capabilities, grow the fan base, and lift profits per fan.

Section 1: An overview of the value chain

Section 2: The shift in capital allocation priorities

Section 3: A brief commentary on return potential and downside risk

An overview of the value chain

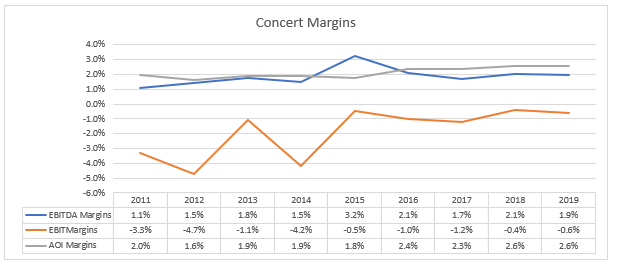

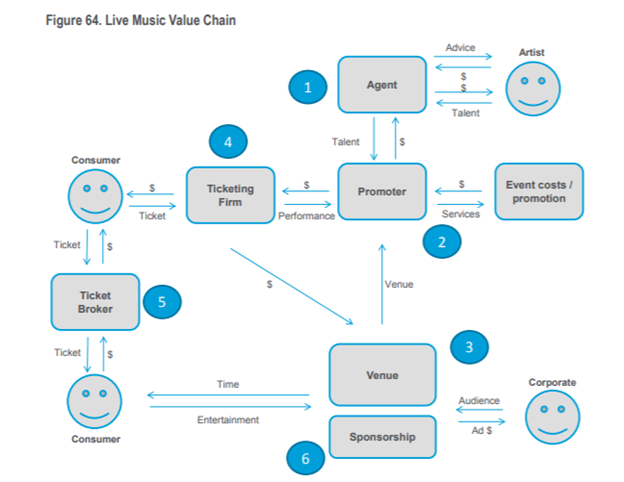

The Concerts segment, which includes their own venues, their role as a promoter for tours and their talent agency, is the lion’s share of Live Nations’ revenue. Their role here is to cater to the insatiable appetite of consumers for experiences and capitalize on the fact that touring has become the largest profit stream for most artists. Live Nations’ concerts business is the behemoth in the industry, putting on 4x the number of concert events versus their closest peer (privately held AEG) and in most years coordinates 90% of the top grossing tours. Analysts expect this segment to do better than $17B in revenue for 2023. Despite this size, the concerts business for most of Live Nation’s history was barely profitable, giving most of the economics to their artists and venue operators.

Obscured behind this seemingly financially unattractive business though has been the moat by which Live Nation would build the high margin sponsorship and ticketing segments. Live Nation uses its scale advantages and supply/demand aggregation in the concerts segment to feed the other profit generating areas of the business. The motion here reminds me a lot of how Amazon used its 1P demand aggregation and physical infrastructure to build out the moat behind which they developed other high margin income streams.

The slide from the 2013 Liberty Investor Day is a good depiction of how this works (and largely remains true to this day). Importantly, think of the middle of the flywheel (circled in blue) as being the promoter/producer of the events. My sense is that the promoter business at Live Nation operates at breakeven or worse to attract the supply of both their own and other artists but puts them in a position to help steer the rest of the value chain. This motion lends itself to natural scale advantages. The footnotes at the bottom are also worth noting and will be something we will touch upon later.

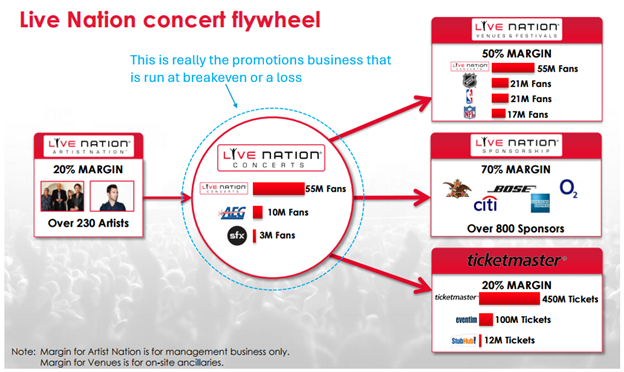

The chart from Citigroup below shows how the money flows in the live events ecosystem. Again, the important point is that the promoter (Live Nation in most cases) sits at the center of the nexus between all the other players…some of which may or may not be affiliated with Live Nation.

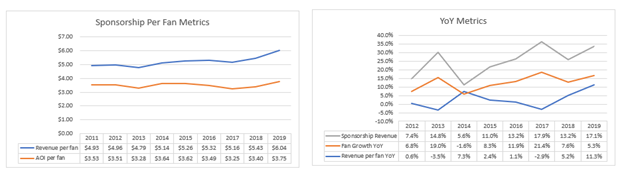

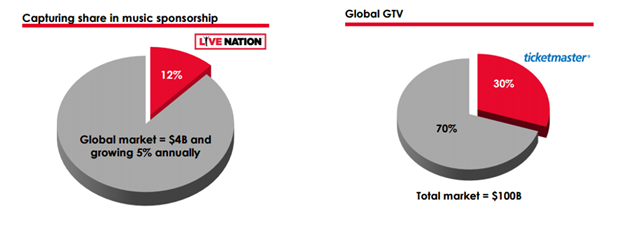

The most profitable piece of this value chain is the Sponsorship business. On its own, the sponsorship operation likely ranks as one of the better physical advertising businesses. Live Nation can deliver ‘eyeballs’ of a captive, engaged and largely happy audience making meaningful memories. In short, it’s a brand marketers wet dream. Control over the supply of these customers and the data collected/resold is a difficult to replicate asset and is a bit of a corned resource. As a result, the economics here are enviable with mid 60% margins. The topline is driven by the volume of fans flowing through the Live Nation ecosystem and the rates at which they are monetized. Note that most of the sponsorship revenue is only collected at Live Nation owned or operated venues.

Coming out of the Great Financial Crisis the sponsorship business was the cash generator for the company. Importantly, these profits would be recycled into the 2010 acquisition of Ticketmaster and support the subsequent heavy periods of re-investment to modernize the Ticketmaster platform. This reinvestment was needed to address the technical debt that had accrued at Ticketmaster and bring the platform into the modern era that could handle increased traffic, mobile delivery, and the ability to have both a primary and secondary offering. While it took a few years for the engine to get started, the combined profits of Ticketmaster and Sponsorships are up 4.5x in 10 years and still have a seemingly long runway for growth.

Ticketmaster has always dominated the primary ticket market. A lot of that reason was because they were the primary ticketing partner for the major sports leagues and the stadium owners, giving them direct access to many of the largest venues available. They won this position by not earning direct fees on the tickets they sold, which further entrenched their incumbency as the key ticketing enabler with the most important venues for major tours.

Moreover, selling tickets is the most crucial step in how almost every player in the live event eco-system gets paid. By being the most scaled player, they are often able to offer the best terms to their artist and venue partners. This includes the ability to offer pre-payments to various parties (including subsidiaries of LiveNation) to help fund the expenses of the tours, the ability to give greater degrees of certainty on the level of sell out (something very important to the venue operator and the artist) and increasingly better data back to all their partners in the music ecosystem.

It is important to recognize that the venue operator is the key decision maker in selecting a primary ticketing vendor. This requires extensive integration with the venue operators’ back-end systems and is usually the lynchpin technology in their stack. There is some talk about the DoJ limiting the length of the exclusivity of certain Ticketmaster contracts with the venues. While this is a scary headline, most of the venue operators I have spoken to, even those that berate the company at times, have admitted that the switching costs are likely not worth it to rip out Ticketmaster. They recognize that having one focused primary ticket seller is the best way to maximize primary sales vs a balkanized system. The data Ticketmaster brings to understanding the concert goer, pricing levers, and marketing effectiveness…not to mention the relationships LiveNation brings to the table by securing touring acts…are very difficult to replace. Even if Ticketmaster saw changes to their exclusivity arrangements, I suspect the majority of the most important venues would still select Ticketmaster as their primary seller.

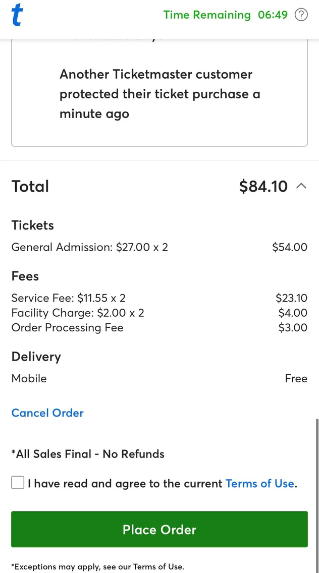

As consumers, we are all too familiar with the dreaded Ticketmaster checkout screen. Consumers rightly feel gutted when a $54 ticket for two is grossed up another 50%+ by fees.

Despite how vilified Ticketmaster is, most of the cost at checkout is being delivered back to the other players in the ecosystem including the artist, the venue and the promoter (some of whom may or may not be associated with Live Nation). In fact, I estimate that Ticketmaster’s true take rate has averaged around 10%, which seems very reasonable versus other take rate businesses like the OTAs in the mid-teens. Ticketmaster may be the focal point of many consumer complaints, but Ticketmaster is acting as a shield behind which the other players in the eco-system earn their economics. Overtime management has signaled that they are going to monetize the data that flows through Ticketmaster by creating non-fee revenue streams which should lessen the reliance on service fees and drop to the bottom line with very high margins.

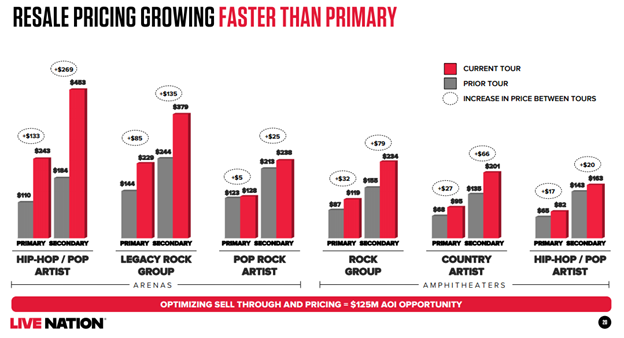

Last, the final major player in the live eco-system is the secondary ticket seller. Ticketmaster did not historically participate in secondary sales, but the technology investments they have made have allowed them entry into this space. It seems to me that they have natural rights to win in this area as they can show both primary and secondary ticket prices side by side, thereby offering the best consumer proposition to the concert goer. Moreover, their understanding of the secondary market can help venue operators and artists better price the primary ticket so that less of the economic value leaks to the secondary market. Currently the secondary ticket market earns ~$5B in annual fees. Live Nations fees in this area are only ~$400M but growing rapidly.

The Turning Point in Capital Allocation

The early part of the 2010’s rightly focused on upgrading Ticketmaster and monetizing the sponsorship business. In 2016 we saw a shift in capital allocation priorities that continues to this day, and I believe is still largely underappreciated. At that time, Ticketmaster’s need for outsized re-investment was approaching its end. In fact, out of the pandemic management found $200M in structural cost savings inside Ticketmaster after nearly a decade of heavy investments. Moreover, the emergence of EDM festivals was booming, giving promoters an opportunity to own very high margin multi-day festivals that did not require year-round maintenance of physical facilities. Seizing this opportunity Live Nation would recycle the healthy profits from Sponsorship and Ticketing back into the Concert segment as Live Nation expanded its own Venue operations both domestically and in important international growth markets that have less developed competition.

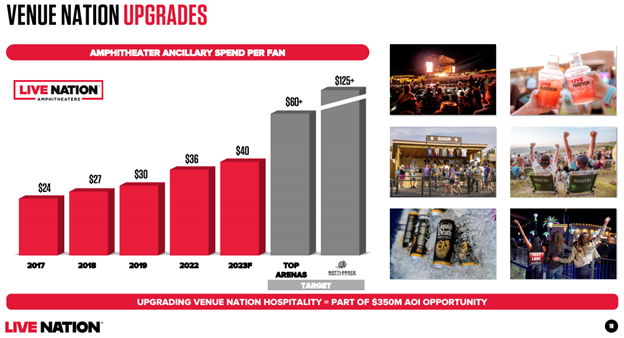

While the business will always have lower margins, these reinvestments drove an acceleration in profit growth as Live Nation monetized their moat. As they dedicated more resources to retrofitting their own venues, and controlling more venues themselves, profit per fan stair stepped higher.

The dollar contribution per fan at their own venues is much more meaningful than those that go through third party venues because they get to fully collect and control all the ancillary fees that occur at an event. These include things like concession sales, parking, and experience upgrades. Recall the exhibit of Live Nation’s flywheel from 2013, the margins for onsite venues are in the mid-50s as anyone who has bought a $20 beer at a concert knows all too well. Venue Nation (the division inside Live Nation which operations the venues) goes beyond just better concession sales, to focusing on designing facilities and offerings that cater to concert goers instead of mixed use stadiums. At the Liberty Investor Day this past November, Live Nation gave further color on what the venue opportunity looks like for them.

Live Nation does not disclose on a regular basis how much of the fan base moves through their own venues. In 2019 they publicly commented that about 43M fans went through their own sites, which was about ~40% of the total fan base. For 2022 they noted on a call that close to 55M fans went through their own venues. Given that they are adding 15-20 venues a year, with each site capable of adding hundreds of thousands to millions of fans per annum, it’s not hard to envision a dramatic uptick in fans flowing through Live Nation owned sites. Importantly, those sites all allow for even deeper control of the rest of the touring value chain. While not Mensa level math, doubling the number of fans flowing through owned or operated venues vs 2019 levels, with better revenue lift per fan and 50%+ flow through margins doesn’t seem like a bad deal.

In fact, Live Nation’s presentation at the 2023 Liberty event highlights that most of the profit growth is going to start coming from the concert segment (blue/green/purple are my comments added).

Importantly, the investments in their own venues also come with other benefits. When Live Nation invests in other promoters or agents, they often will deliver cash up front for a majority stake and a put/call arrangement on the back end. While this aligns the incentives, it is a bit more capital intensive. The building out of venues though is largely financed with construction loans and pre-sales. Additionally, the cash flow comes back to Live Nation in a much cleaner fashion which should increase the conversion of AOI to actual owners’ earnings. Moreover, as you add a physical presence in many of the international markets, you add to the demand aggregation capabilities of the company to service their global touring artists. This further builds out the key physical distribution moat that Live Nation brings to the table. Lastly, as the profit mix moves more towards venues and sponsorship there is less exposure to the regulatory risks of Ticketmaster.

CEO Michael Rapino outlined just how attractive investments in Venue Nation can be during a presentation at BofA this last September. While the answer is long-winded it is worth reviewing (emphasis added):

“We've always been in the venue business. Amphitheaters in America was the easy entry point for most promoters back in the day. And we have a bunch of theaters in clubs and incredible businesses. They drive huge returns for our sponsorship, our ticketing, the vertical machine. So we love the venue business. In COVID, we started to change our strategy slightly and merge all of our businesses on this venue nation because we're starting to really see that every developer in town wanted a live venue. They didn't want a movie theater anymore, but they want a live venue. Every developer wanted to build that LA live. And every rich billionaire that had a sports team wanted to take his arena and build retail and do what Atlanta did, right? … But up until then, we were kind of the tail on the dog. We'd be the dumb guy that would like let the developer come in, maybe SMG built the building and we come to the final pitch and say, well, 100 shows in and get a rebate.

We start to realize our content was really valuable…we should have built the venue, we should operate the venue and fill the venue. That's the best return on our capital when we do that kind of triple win. So then you just got to look at white space. So America was always a bit complicated because there's so many great NBA, NHL NFL owners that have their own stadiums and arenas, you really couldn't look many opportunities. Austin was that rare market where there wasn't an arena. We built an arena. It's a home run with OVG. It's a 30-plus percent IRR.

And we look at that model and to give you kind of capital ideas you looked at them all like that, what the banks love about a model like that is just really long-term committed capital. So we're going to launch in Austin arena. It was about $350 million to build, a $75 million equity check. Banks love that there's a 10-, 20-year committed revenue around boxes, name and title premium seats. So you look at a model like Austin, we're preselling sponsorship and name and titles 3 years out. We actually never even wrote our $75 million equity check. We had more revenue come in, self-finance the building, open up the building and you get an incredible return. So I say that because I know there's some panic sometimes in building and capital allocation.

So we look at models like that and where we see the white space, obviously, is international. Every market city that we look at probably has a beautiful soccer or football stadium for their local team but they don't have an arena. There is no NBA, there's no NHL. It's probably been an old arena or a rusty arena. So we have Arena now in Dublin. We bought a arena in Amsterdam. We bought one in Lisbon….

…..And in the last year, we've seen it. We've been in that pitch in that foreign market where CTS is pitching kind of the traditional OVG venue developers and us, and we're winning because we get to walk in and say, we know how to build the $300 million, $400 million arena. And by the way, more importantly, we're going to fill this thing through content. So kind of being in that front seat as the developer and operator owner over time. We think there's great returns here…

….Now there's 2 ways we look at capital allocation. At minimum, we want a 20% return. They can be up to 30% on some home runs like Austin and even up to 40% on some of our rev-gen in capital. So if you look at our current model, now 80% of our ReVCap [revenue generating capex], we're going to spend in CapEx this year, that $450 million is going to be rev generating. Joe and I will go through the next month, where we probably have 100 opportunities where our operators will come to us on Rev Gev. Hi, I've got the amphitheater in St. Louis, and I got a crappy room like this, but if I get $400,000, I can turn into the VIP Club and sell a new 1,000 members. We did this in Toronto this year, where we had a room like this that was going to be given away to sponsors.

We said, no, let's make it a membership club. We sold out 100 members at $5,000 overnight, spend a couple of hundred grand to renovate. So huge opportunity in all of those. Anything we're doing on site is probably because we got a room that's selling a face value ticket for low, and we think we can upgrade it or upgrade this concession stands because we can sell more food and beverage….

….If you look at America and you really look at Live Nation and say, what was its kind of core strength on what we built this off, it was our 40 amphitheaters. We were able to have a platform where we can build our ticketing our sponsorship. We didn't have that in international. When we buy a promoter or a festival, it's a slower entry. When you roll into a market and buy and build an arena kind of propel all those other pieces really fast. We weren't able to do that in America because like I said, there's MSG. The main market was already probably covered. Internationally, we think we can actually excel our growth because you can have that one pinnacle venue that really excels your bottom line and your entry.”

There are some shareholders that rightly wonder if the increasing rate of profit growth means that Live Nation will start returning cash to shareholders. I remain in the camp that if you can continue to deploy low risk projects with 20-40% IRRs that further extend the moat, then I would prefer those earnings to be re-invested back into the business.

That is exactly how I see the build out happening with Venue Nation. Prior to Covid, we already saw how the deployment of capital back into their own venues lifted AOI per fan in the concert segment. According to consensus estimates, the street is already at $12.50 of AOI per fan, a 25% lift from pre-pandemic. Going forward, I expect this rate to accelerate, adding ~$2 of AOI per fan in the concert segment, a $1 of AOI in ticketing (primary growth, secondary ticket expansion & non-fee revenue) and a $1 of AOI from sponsorships (mostly on the back of CPM inflation from greater scale). As we watch the thesis play out, the AOI per fan metric is going to be the KPI to monitor.

A Mental Model for Returns

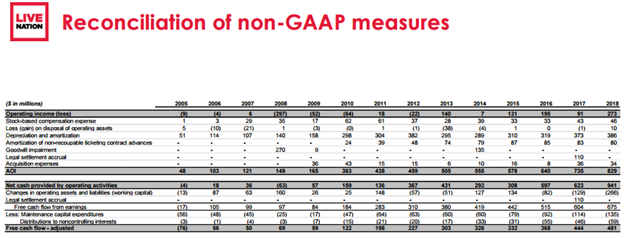

Thus far I have avoided the sticky topic of diving deeply into Live Nations’ accounting. Frankly, this piece would be 3x as long if I went through the nuances. Skeptics are frankly right to point out that management’s Adjusted Operating Income number is not shareholder profits, that managements’ definition of Free Cash Flow is not traditional and how much cash on the balance sheet is Live Nation’s is debatable (I think you can count better than half of it as being truly Live Nations’).

While I am sympathetic to this viewpoint, I do believe that the AOI measures provided by the company are an excellent indicator of the financial health of the business and the returns they are generating. Moreover, you do not need to use these measures as inputs for valuation despite their usefulness in gauging the progress of the company.

For what it is worth, my own definition of owner’s earnings focuses on cash flow, charges the company for its investments and distributions to minority interests, fully charges both maintenance and revenue generating capex and assumes an ongoing need for some level of acquisition expenses. My owner’s earnings conversion ratio of AOI had been moving higher since 2016 as the reinvestment into venues gathered steam. I suspect that as more of the profit stream is tied to the venues, there is less investment needed in Ticketmaster and the Sponsorship business continues to scale that we will see a further increase in this conversion ratio. You should do your own work here to determine what profits you believe belong to shareholders.

While AOI/EBITDA are not shareholder profits, prior to the pandemic and the subsequent whipsaw in financials, it was very clear that the stock price largely followed the growth of EBITDA. In fact, during that period we saw a lift in multiples as the strategy proved out.

If management is to be believed, AOI should grow at LDD rates over the medium term. An easy mental model is that if you burn the share count at 2% per annum and hold the multiple steady one should earn a 10% return.

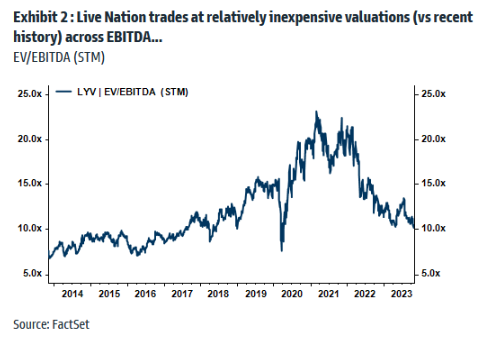

That said, GS recently pointed out that Live Nation is trading at near trough multiples.

Perhaps it is not unreasonable to assume that if the DoJ investigation passes without severe negative consequences (which I think is likely), the AOI per fan truly inflects higher, and the return on capital of the business improves. If so, then the earnings stream may deserve to be capitalized at higher multiple.

The rub here is contemplating the downside. While I agree with managements’ thesis that live events are better insulated from macro-economic shock than large ticket consumer durables, the space is not totally immune. If we were to see a vanilla recession, it is likely that there would be a drawdown in the reported results, a push out in the earnings power and thus IRRs. At this point, if Covid couldn’t kill the business I do not think some general economic weakness would be catastrophic.

What is more difficult to bracket is the likelihood that the DoJ or congress steps in to attempt to dent Live Nations market power. As mentioned earlier, the rumor mill is suggesting that we could see modifications to the exclusivity of Ticketmaster’s arrangement with various venues. While I think Ticketmaster would compete quite well even without these exclusive contracts, there is the possibility that my assessment in this area is wrong.

Historically, only 30-45% of all fee bearing tickets sold were tied to Live Nations operated events. If Live Nation were to lose half the other venues over time perhaps that would cut Ticketmaster’s AOI potential by roughly half and be a $500M headwind to total company AOI. Using rough math, that might put future EBITDA levels between $2 to $2.5B depending on what the macro-economic situation looked like at that time. Perhaps 9x that level of EBITDA is a reasonable downside case and could see the stock trade in the low $60 to $70 range. This would be a bad outcome for sure and I suspect the stock price would react violently to the downside as this potential news flow was priced in. That said, there are prices where I would feel comfortable risking $20 of downside risk on a low probability event to align myself with an entrenched business that appears to be on the verge of inflecting profits higher.

Disclosure: At the time of writing, accounts associated with the author owned shares of AMZN. The author may have bought, sold or exited any of the companies mentioned in this post without notice.